Number Systems and Character Encodings

In this chapter, we will dive into the fundamental concepts of number systems and character encodings — a crucial foundation for everything you will encounter in the world of computers.

Number Systems

Digits and Bases

You may already know that there are various number systems, and the same number can be represented differently in each one.

The most common number system is the decimal (base-10) system, which humans typically use to represent numbers.

However, computers cannot represent such a wide range of digits because they are typically designed with circuitry that operates in two states: on (1) or off (0). Therefore, computers represent numbers using the binary (base-2) number system internally. Additionally, a lot of times (especially when dealing with cryptography and networking) we need the hexadecimal (base-16) number system. Therefore, understanding how number systems work in general is crucial.

Different number systems are distinguished by the digits they use. Digits are the individual units that you can use to "create" a number.

The base of a number system is the number of digits available in it.

For example, the decimal system has the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Therefore, the base of the decimal system is 10.

The binary system has only 2 digits, namely 0 and 1.

Therefore, the base of the binary system is 2.

The hexadecimal system has base 16. This leads to a problem - after all, we only have 10 "conventional digits" (0-9).

The solution to this is simple - we use the letters A-F for the last digits.

The digits of the hexadecimal system are therefore 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A (for 10), B (for 11), C (for 12), D (for 13), E (for 14), F (for 15).

Creating Numbers

How do we create a number in a number system?

Consider the number 7423 in the decimal system.

In high school, you probably learned that each digit has a "place value".

For example, the digit 3 is in the ones position and therefore has the place value 3.

The digit 2 is in the tens position and, therefore, has the place value 2 * 10, i.e. 20.

The digit 4 is in the hundreds position and, therefore, has the place value 4 * 100, i.e. 400.

Finally, the digit 7 is in the thousands position and, therefore, has the place value 7 * 1000, i.e. 7000.

The "value" of the number 7423 is then the sum of all the place values of the digits, i.e.

3 + 20 + 400 + 7000 = 7423

In the decimal system, you do not actually need to laboriously compute the value of the number to get it - you can simply look at the number itself.

However, in the binary system, it is different.

Consider the number 1101 in the binary system.

Here, each digit also has a position, but the place values are computed differently.

The multipliers are no longer powers of ten (i.e. 1, 10, 100 and 1000), but powers of two (i.e. 1, 2, 4 and 8).

In our example, we have a digit 1 in the ones position - it has the place value 1.

The digit 0 is in the "twos" position and, therefore, has the place value 0 * 2, i.e. 0.

The next digit 1 is in the "fours" position and, therefore, has the place value 1 * 4, i.e. 4.

Finally, the digit 1 is in the "eights" position and, therefore, has the place value 1 * 8, i.e. 8.

Therefore, the value of the number 1101 would be:

1 + 4 + 8 = 13

How could we approach this for an arbitrary number and number system?

Looking at our examples, we see that the value of a number is the sum of its place values:

V = p_0 + p_1 + ... + p_n

where p_i is the place value of the ith digit.

Each place value is computed by multiplying the digit with the corresponding multiplier. It is easy to see that the multiplier is simply the base raised to the power of the position of the digit.

Therefore, you can calculate the value of a number in any given number system via the following formula:

V = d_0 * b^0 + d_1 * b^1 + ... + d_n * b^n

In this formula:

Vrepresents the value of the numbernis the number of digits in the number (for example the number7423has 4 digits)d_iis the digit in the i-th position from the right (0-indexed), for example given the number7423,d_1would be2andd_2would be4bis the base of the number system

Let's apply this formula to our examples.

First, we will calculate the value of 7423 in base 10.

Here, we have n = 4 (since we have 4 digits).

The digits are d_0 = 3, d_1 = 2, d_2 = 4 and d_3 = 7.

And since the base is b = 10, the multipliers will be b^0 = 10^0 = 1, b^1 = 10^1 = 10, b^2 = 10^2 = 100 and b^3 = 10^3 = 1000, respectively.

Therefore, we get:

V = d_0 * b^0 + d_1 * b^1 + d_2 * b^2 + d_3 * b^3 = 3 * 1 + 2 * 10 + 4 * 100 + 7 * 1000 = 7423

Second, let's calculate the value of 1101 in base 2.

Here, we have n = 4 (since we have 4 digits).

The digits are d_0 = 1, d_1 = 0, d_2 = 1 and d_3 = 1.

And since the base is b = 2, the multipliers will be b^0 = 2^0 = 1, b^1 = 2^1 = 2, b^2 = 2^2 = 4 and b^3 = 2^3 = 8, respectively.

Therefore, we get:

V = d_0 * b^0 + d_1 * b^1 + d_2 * b^2 + d_3 * b^3 = 1 * 1 + 0 * 2 + 1 * 4 + 1 * 8 = 13

As you might have already guessed the binary system is not really human readable, especially because it needs much more space than the corresponding decimal number.

Therefore, we often represent digital data using the hexadecimal system. The general formula for calculating values of hexadecimal numbers is the same as for every other number system.

Consider the number 5fa8:

V = d_0 * b^0 + d_1 * b^1 + d_2 * b^2 + d_3 * b^3 = 8 * 1 + 10 * 16 + 15 * 16^2 + 5 * 16^3 = 24488

We use the hexadecimal number system rather than the decimal system for digital data representation because the relationship between base 16 and base 2 is much more straightforward and convenient than that between base 10 and base 2.

This is because you represent the numbers 0 to 15 using either one hexadecimal digit (0 to F) or four binary digits (0000 to 1111).

This means that one byte (eight bits) can be represented using two hexadecimal numbers.

We have introduced the most common number systems:

base-10- the ones humans usebase-2- this is how computers actually represent digital database-16- a smaller and more readable representation of digital data

There are numerous other number systems, such as the base 8 system, also known as the octal system, which is occasionally used. Additionally, by applying the same method, you can construct various other systems, like base 6 or base 11. However, these systems do not have real practical applications.

Unicode

In the previous chapter, we explored how numbers used by humans are represented inside a computer and how to programmatically convert from the computer's binary representation to the decimal system, that we are all familiar with. However, you are likely reading this text not as a series of numbers, but as meaningful words. So, how do we go from numbers to text?

To bridge this gap, we need a system that assigns a unique number to each character. In the early days of computing, systems like ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) were developed, but they were limited to representing a small set of characters (mostly English letters, digits and some other things).

ASCII

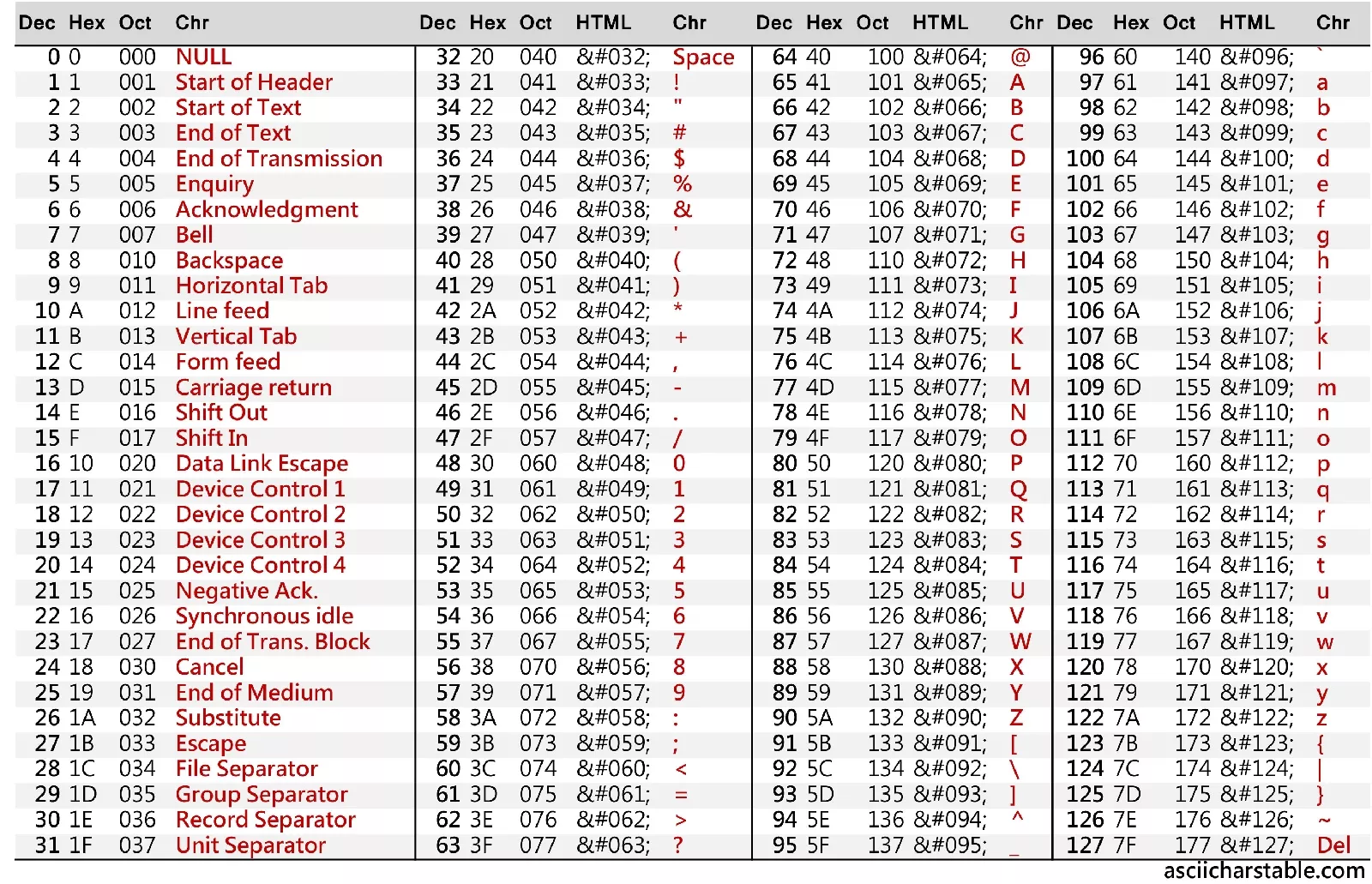

Here is how an ASCII table looks:

Basically, an ASCII table is a one-to-one mapping of a number to a specific character.

Whenever it appears that we are working with a character, we are actually working with its corresponding number, and the computer neatly treats the number as if it were the character.

Let's say you have a text file with the sentence: Hello world!.

Try to find the representation of this sentence in ASCII using hex numbers:

Hello, world!

The solution is

48 65 6C 6C 6F 2C 20 77 6F 72 6C 64 21

Or - in binary:

01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00101100 00100000 01110111 01101111 01110010 01101100 01100100 00100001

This is the moment where you realize why we usually write things in the hexadecimal representation and not in the binary representation.

The ASCII system was straightforward and nice, but programmers soon realized that English is not the only language in the world. Soon, the limitations of ASCII became apparent. Different languages, with their unique characters and symbols, could not be adequately represented. This limitation led to the development of Unicode, a universal character encoding system.

This is an extremely shortened "history" of Unicode. In reality there were a lot of standards in between. However, nowadays almost everyone uses Unicode, and since this is a book about Linux rather than its history, we will gloss over them.

Unicode

So what is Unicode?

The most important part of Unicode is another one-to-one mapping between characters and numbers.

This is similar to ASCII, except that the character table is giant - version 15.1 defines 149813 (!) characters including constructs like emojis.

Such a number is called a code point.

The entire set of code points is divided into 17 character planes, each consisting of 65,536 code points. These planes are indexed from 0 to 16.

The plane 0 is called the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP for short) and ranges from U+0000 to U+FFFF.

It contains the most commonly used characters, including most characters from the most common modern languages, punctuation, and many symbols.

Most of the characters that you encounter in everyday text are in the BMP.

Planes 1 to 16 are the supplementary planes and range from U+010000 to U+10FFFF.

They include less commonly used characters, historic languages, various symbols, and emojis.

For example, Plane 1 is the Supplementary Multilingual Plane (SMP for short), which includes ancient languages and emoji characters.

Importantly, a Unicode code point is an abstract number and doesn't directly specify how that number is actually stored in a computer's memory. This job is managed by encodings.

The Unicode standard itself defines three encodings - UTF-8, UTF-16 and UTF-32.

UTF-8

UTF-8 (8-bit Unicode Transformation Format) is a variable-length encoding that can use 1 to 4 bytes for each character. It's designed to be backward compatible with ASCII, which means that the first 128 characters in Unicode (which corresponds to standard ASCII characters) are represented in UTF-8 using exactly the same single byte, making it efficient for English and other Latin-based languages.

Examples:

- Character

A(code pointU+0041): In UTF-8,Ais represented as 41 in hexadecimal, which is the same as its ASCII representation. - Character

€(code pointU+20AC): This character is beyond the ASCII range and is encoded in UTF-8 asE2 82 ACin hexadecimal, using three bytes.

UTF-16

UTF-16 (16-bit Unicode Transformation Format) uses 2 bytes for most characters but extends to 4 bytes for characters outside the Basic Multilingual Plane (more on this in a minute). It is often more efficient than UTF-8 for files that require a large number of non-Latin characters.

Examples:

- Character

A(code pointU+0041): In UTF-16,Ais represented as00 41in hexadecimal, using two bytes. - Character

𐐷(Deseret Capital Letter Ew, code pointU+10437): This character is in a supplementary plane and is encoded in UTF-16 as a surrogate pairD801 DC37in hexadecimal, using four bytes.

In the UTF-16 encoding, characters outside the BMP require a special encoding mechanism known as surrogate pairs. A surrogate pair consists of two 16-bit code units: a high surrogate and a low surrogate.

Surrogate Ranges

- High Surrogates: Range from U+D800 to U+DBFF (1,024 possible values).

- Low Surrogates: Range from U+DC00 to U+DFFF (1,024 possible values).

To encode a character outside the BMP using surrogate pairs, the following steps are taken:

- Subtract 0x10000 from the character's Unicode code point. This aligns the code point to the start of the supplementary planes.

- Represent the result as a 20-bit binary number.

- Split this 20-bit number into two parts: the high 10 bits and the low 10 bits.

- Add the high 10 bits to 0xD800 to get the high surrogate.

- Add the low 10 bits to 0xDC00 to get the low surrogate.

For example, here is how we would encode the '𐐷' character (U+10437):

-

Subtract 0x10000 from U+10437: U+10437 - U+10000 = U+00437

-

Represent U+00437 as a 20-bit binary number: U+00437 in binary is 0000 0100 0011 0111.

-

Split into high and low 10 bits: High 10 bits: 0000 0100 00 (binary) = 0x0040 (hexadecimal) Low 10 bits: 11 0111 (binary) = 0x0037 (hexadecimal)

-

Calculate the high surrogate: 0xD800 + 0x0040 = 0xD840

-

Calculate the low surrogate: 0xDC00 + 0x0037 = 0xDC37

Therefore, the UTF-16 encoding of '𐐷' (U+10437) is the surrogate pair 0xD840 0xDC37.

Try encoding 😊 (U+1F60A) using surrogate pairs (the result should be 0xD83D 0xDE0A).

UTF-32

UTF-32 (32-bit Unicode Transformation Format) is a Unicode encoding that uses a fixed length of four bytes (32 bits) for every character. Unlike UTF-8 and UTF-16, which are variable-length encodings, UTF-32 has the characteristic of using a consistent length for all characters, making it simpler in terms of understanding and handling character encoding.

Let's take the character 'A' (U+0041) as an example:

In UTF-32, 'A' is represented as 00 00 00 41 in hexadecimal. The Unicode code point U+0041 is directly placed in the 32-bit unit, with leading zeros to fill the four bytes.

Another example is the character '😊' (U+1F60A):

In UTF-32, '😊' is represented as 00 01 F6 0A in hexadecimal. The Unicode code point U+1F60A is directly placed in the 32-bit unit, again with leading zeros.